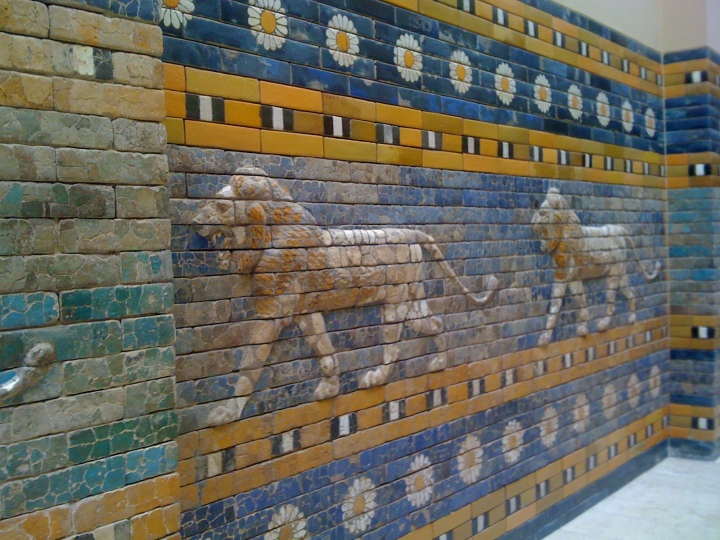

From the entrance lobby of the museum, I climbed a short stairwell and then had to pause for a moment to let my eyes adjust. Not to the light or the dark, but to the grandeur. Without fanfare, I was suddenly on one of the great processional ways in history and to my right rose the great north gate of Babylon.

The walls of the gateway are blue-glazed and decorated with flower motifs and processions of animals. Above the ranks of bulls, which are the symbol of the Babylonian god Adad, are rows of less recognisable beasts. These are the Mushhushshu. This mythical chimaera is dragon-like with the head and body of a serpent, the forelegs of a lion, the hind legs and talons of an eagle and the sting of a scorpion in its tail. It too symbolises a Babylonian god, Marduk, and looks like an animal to be reckoned with.

For the most part, the animals are original and they are made not just of glazed and coloured bricks, but are also moulded in low relief. Standing proud of the wall they are composed of mostly original bricks. Their colours are slightly faded and many are cracked and chipped. Between the animals there are slightly brighter blue glazed bricks whose crack-free surfaces suggest they are 20th century additions. This mixture of old and new recreates the great northern gateway of ancient Babylon. This Ishtar Gate is named after the Babylonian goddess of love and war—how appropriate to pair those two in one deity—and, along with the great processional way, now stands in the Pergammon Museum in Berlin.

Painstakingly excavated, catalogued, washed, and pieced back together, German archeologists brought their prize find home to their capital after the First World War where it was rebuilt brick by brick and has been delighting open-mouthed visitors ever since.

But what has been created is not necessarily a vision of an ancient reality. Visitors to the museum are invited to enter a time warp — to walk down the great processional way, lined with snarling lions, and through the Ishtar Gate into the mighty citadel of Babylon, as they would have done in around 600 BCE. The imagined middle eastern sun might be shining on blue, white and yellow glazed bricks and there is noise and excitement in foreign tongues along the path, as there probably always was, as new visitors to the city approach the entrance. It is certainly true that as you walk along the bustling corridor of the Pergammon museum, past the beautiful tiled walls in their jewel like colours and on into the room where the front section of the northern gate has been reconstructed, that you are experiencing as close as possible to the vision set out above, but it is not quite what it seems.

In the museum we find ourselves in a world more of manufactured memory than recreated past. There are many literally missing pieces to this particular jigsaw and the gaps have been filled with reproductions, designed to blend almost seamlessly with the originals. There is a lot of educated guesswork at play here and what has been recreated is, we are told quite openly, largely dictated by the dimensions of the original museum building. The processional way is around a third of its real width and the height of the glazed crenellations is set by the height of the roof rather than any archeological estimation. The gate itself is only the front section, and the larger rear section would have required a museum twice the height to recreate and presumably a great deal more newly-fired tiles.

So, what we see today is a scaled down and touched up image of what it might have been. The grandeur and beauty, already admittedly overwhelming, would have been at least twice as great again and the missing tiles have been replaced to complete the glazed facades. Is this deception or is this a justified fabrication? What we are shown today in the museum is clearly a version of what might have been, but to talk of deception is unfair. The archeology is at best sketchy, and there has been no deliberate intent to create something that never was, but rather to present a reasonable and practicable approximation. And the result is wondrous.

A recreated past; a manufactured memory; a best attempt: these are what the Pergammon Museum offers. The lions, bulls and serpent-headed dragons of the processional way and the Ishtar Gate were built to impress and intimidate visitors more than 2,500 years ago. If what has been recreated today still makes the visitor stop and gasp, isn’t that the intent? Even if the dimensions have been adjusted and the configuration of the bricks is nothing more than an estimate, perhaps it is the emotion that is authentic. Visitors to ancient Babylon were awe-struck. So too are visitors to the Pergammon Museum in Berlin and I suspect they always will be.

© Allan Gaw 2016

My latest book…

Testing the Waters

Lessons from the History of Drug Research

What can we learn from the past that may be relevant to modern drug research?

http://www.amazon.com/Testing-Waters-Lessons-History-Research-ebook/dp/B01AXBM0WQ/

My other books currently available on kindle: